"What's a guy like you doing in a place like this?"

How I chose a career in funeral directing.

People frequently ask me what life events led to my decision to be a funeral director. Since this question is usually asked as an aside, I tend to try to be as concise as possible. What I typically say is “Family.”

My Grandmother's family, pictured just before her birth. Left to right, back to front: Bill, Rose, Johnnie, Manuel, Great Grandma Rosa, Leo, Great Grandpa John, Mary, Henry, Ed, Isabel, Ben. California, 1922.

Mine is large and Azorean Portuguese American. Roman Catholic to the core, our family’s funerals are elaborate, days-long observances. My grandmother Paulina was the eleventh of eleven children, so as I was growing up, these experiences were as frequent as once a year. A viewing with visitation, a Rosary, a pre-funeral family gathering around the casket to watch the closing of the lid before processing as a group to the church for Mass, then again to the cemetery for a committal service, then gathering for a reception and shared meal… it was really rather involved. But it was tradition, and it meant something, and I didn’t really know there was any other way of going about it. So that’s what we did.

The first funeral I remember attending was when I was four years old. My great-aunt Leonor had died in her nineties, and after a funeral Mass at our family’s home parish, she was being buried next to Uncle Johnnie at Garden of Memories Cemetery.

Before the graveside committal service began, the priest approached me and asked me if I would help him—he needed someone to hold his bottle of Holy Water during his opening remarks, and then hand him the bottle when he reached for it for the Sprinkling Rite. Would I like to help him? Who was I to deny a priest? Executing this task with deliberate precision, I was proud of helping Aunt Lee get to heaven. My life’s trajectory was set.

Another important part of growing up for me was tagging along with my grandmother and her sister, my great aunt Mimi. They had both lost husbands in the 1970’s and the pride they took in their identities as widows brought them close. They would periodically visit the cemetery to clean family headstones and place flowers. I was frequently brought along to help.

Grandma Paulina and Grandpa Bob Schauman on their wedding day. Salinas, California. 1946.

One visit to the cemetery sticks out in my mind in particular. Mimi was leaving flowers at the grave of her husband. She had a companion headstone placed there—a wider stone that the both of them would eventually share. “CHEADLE” was engraved across the top, Uncle Leland’s name and dates were on the left, and the right was blank. “You see,” Mimi explained calmly, “Uncle Leland was buried here after he died.” Then she shifted her focus to the empty grave next to him. “And, one day, after Mimi dies, she’ll be buried there.”

I think that’s when it started to occur to me: Everyone who’s alive now, one day won’t be. And death is not something we avoid, but it IS something we can prepare for. She didn’t make it sound scary and traumatic, or like some dreadful thing that must never be discussed—she modeled to me an even-headed, gentle attitude toward the truth that death is the culmination of each life.

Leland and Mimi, Santa Maria, California. 1954.

The “one day” she prepared me for was not many years away. Within a couple of weeks of her cancer diagnosis, Mimi died surrounded by extended family. I was twelve years old, and it was the first death I would be present to experience. As Mimi didn’t have any children, it was my mother and grandmother who would make arrangements and settle Mimi’s final business affairs. They made a decision that would have phenomenal long-term implications: They brought me to the funeral home for the arrangement conference.

Before going to meet the funeral director, my mother, grandmother and I went to Mimi’s home to get some important papers, as well as some clothing and jewelry for her viewing. It was immediately clear to us that she knew she wasn’t well—an envelope addressed to “My Survivors” was left for us on her table. This envelope included the deed to her cemetery plot, and a letter with some details for the obituary about her life & career. She also wrote to us about the flowers and music she wanted at her services, and what she wanted to wear.

Mimi. August 1979.

We took these items (and a recent photograph) with us to the funeral home to arrange the details. Even before entering the building, I could tell that we had arrived at a space set apart—the front door was locked, and we had to ring a bell to be permitted entry, escorted by staff at all times. It wasn’t unwelcoming so much as it was very formal, almost Victorian.

We met our funeral director, and provided him with biographical information for Mimi’s death certificate, and explained to him our Portuguese Catholic custom—viewing, Rosary, Funeral, and Committal.

A casket was ordered. Family cars were reserved and chauffeurs were hired. Although she picked out the music for the Mass, we still needed to decide on scriptural readings. A eulogy was composed, motor escorts and reception catering were arranged, aunts and uncles were flown in and accommodated. Mimi’s life was celebrated, over the next few days, in a way we felt was proper and necessary. Needless to say, the elaborate planning of this event stuck with me.

Jessica Mitford's American Way of Death Revisited.

My curiosity in this subject area continued over the course of the next few years. I remember I was 15 years old when I first read Jessica Mitford’s American Way of Death Revisited. It opened up to me the idea that a simpler way was possible, and just as dignified. It also brought to my attention that not all funeral establishments were as professional and reputable as our local directors had been. I learned that there were families being taken advantage of financially by way of emotional manipulation and subliminal marketing techniques, or even a simple lack of understanding of the rights and responsibilities that come along with a family death. This seemed to me to be a terrible injustice, and I found it extraordinarily troubling. As I went through high school and college, exposé pieces in the media brought our collective attention to problems in the industry like laws being broken and prepayment funds being stolen.

I realized I wanted a career that would make a difference, that would keep families safe from anything untoward, but I wasn’t sure how to do that. I had considered family law, to assist with end-of-life documents, but that was too far removed from the arrangement room. Was there such a thing as a deathcare doula? Not really. It wasn’t until I finished my bachelor’s degree that I decided to join the funeral industry myself, so I could be in a position to advocate for the respect, compassion, and ethical treatment that client families deserve. And that is why I became a funeral director.

Uncle Leland and Aunt Mimi's headstone, Salinas, California.

It is with much gratitude that I work for The Co-op Funeral Home owned by the members of People’s Memorial Association. The organization’s vision is that all might have access to funeral options in line with individual tastes and preferences; it’s this type of vision I’ve always found myself personally and professionally aligned with. Mitford herself admired and endorsed both PMA and her local Funeral Consumer’s Alliance. As it was her writing that moved me in this direction to begin with, my work here feels like a contribution to her vision of ethical and professional funeral and memorial options at affordable prices. And working to fulfil that need is the most satisfying job I could possibly ask for.

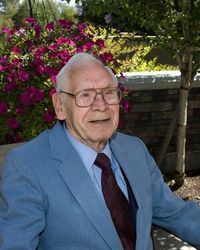

Chris Ronk is a licensed funeral director. He has worked in the funeral industry since 2006.